Jane Falkenstein's house looks like any other single-family home in the Salt River Valley of Arizona — beige stucco, gravel lawn, a two-car garage, a shaggy palm tree.

The path to her front door gives the first indication that her home is something special. A mature plumeria tree with dozens of fragrant yellow and white flowers wraps around the footpath. Her open windows emit the sounds of squawking birds, which carry clear to the end of the cul-de-sac. Above her doorbell is a stained-glass window that depicts a green Amazon parrot.

These eccentricities portend, though hardly prepare a visitor for, the small miracle tucked away in Ms Falkenstein’s backyard — a dense jungle of rare Latin American and Asian fruit trees in one of the hottest and most arid urban environments in North America.

The architect of this backyard ecosystem was her husband, Dr Alois Falkenstein Jr, a German immigrant, US Air Force veteran and ophthalmologist who began cultivating fruit plants that most Arizonans had never tasted. His harvests included jabuticaba berries, longans, loquat plums, pluerries, white sapotes, Keitt mangoes, finger limes, doughnut peaches, bergamot oranges and Fujian Bai Mi figs, a species known colloquially as Nixon peace figs after Mao Zedong gave cuttings of the plant as a peace offering during the president’s trip to China in 1972.

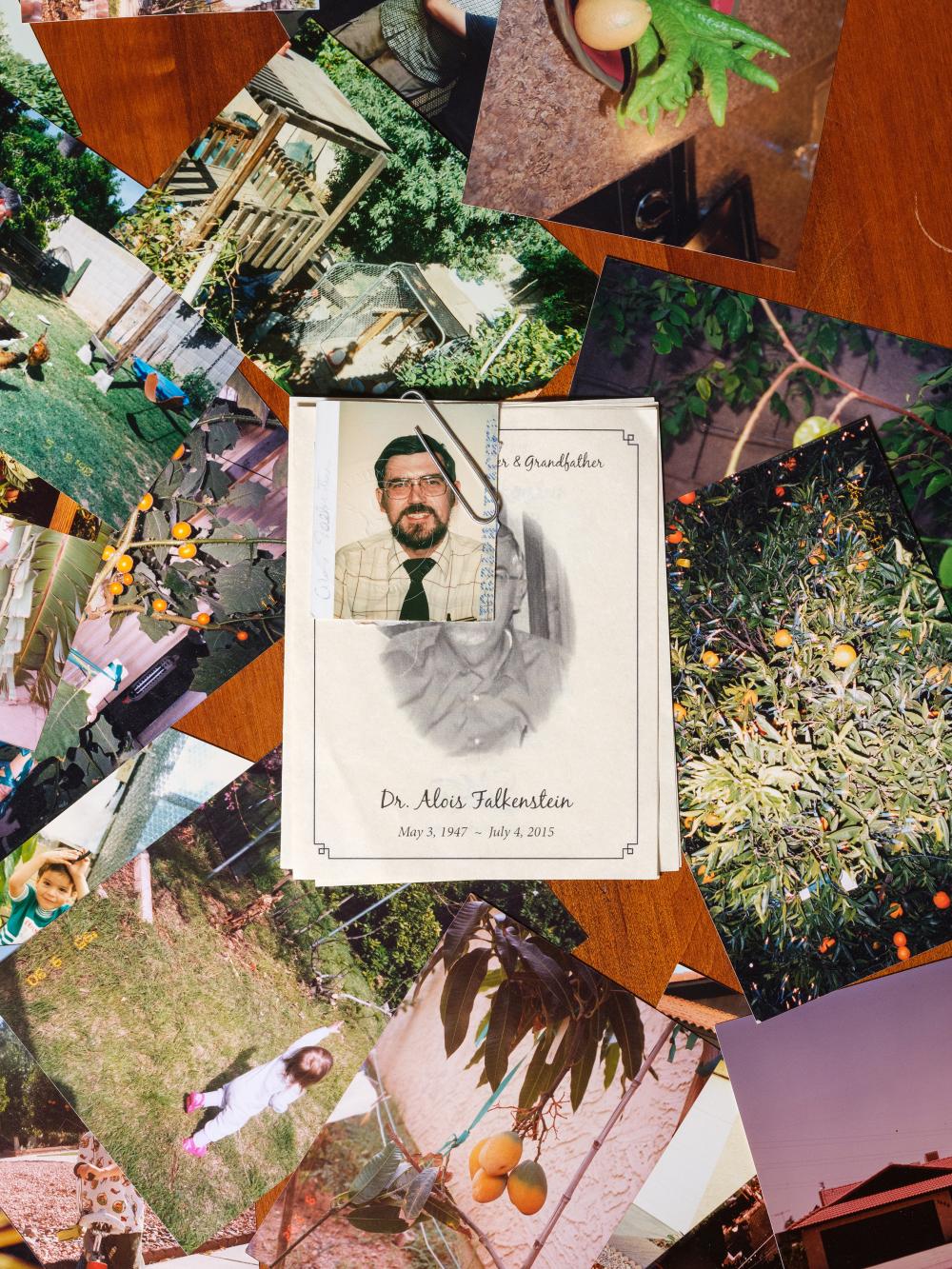

Alois Falkenstein, who died in 2015 at age 68, was fluent in German and could read and write in several languages, said Jane Falkenstein, 73, adding that these skills proved useful in his work as an in-flight physician and a translator for diplomats.

The funeral programme for Dr Alois Falkenstein, who died of cancer in 2015, surrounded by photos of plants that he grew. David Blakeman/nyt

In his free time, Dr Al, as he was known, studied plants. “He wrote numerous articles about gibberellic acid and the growth patterns of fruit plants,” she said. “He was a curious person and a quick learner.”

Falkenstein broke ground on his backyard garden when the couple moved into the house in 1981; he was frustrated with the lack of tropical fruit in nearby grocery stores. Years later, he travelled to San Diego with his sons, Alexander and Chris, to research tropical fruit species over three-day weekends.

“My brother and I knew these trips weren’t meant to be fancy — they were meant to teach us things,” recalled Alexander, 34. “He would take us to museums and gardeners’ homes. He would talk to rare fruit growers about their favourite books and ideas. I could tell that there was a lot of mutual respect and admiration there.”

These trips enabled Falkenstein to transport dozens of plant cuttings back to the desert for propagation, and to apply his friends’ collective knowledge to his fledgling garden. Bit by bit, he transformed the barren dirt into a tropical microclimate. He built rows of shaded trellises, a chicken coop, a tool shed and a large greenhouse that his friends jokingly referred to as his “shop of horrors”.

The greenhouse was his laboratory and staging ground, a carefully maintained space for the delicate process of raising tropical plants in the desert. Many of these plant varieties were the progeny of his frustrating, pre-internet experiments in cross-pollination. When his dragon-fruit flowers opened up for the evening, he would put on a headlamp, retrieve one of his pollen containers from the freezer, and meticulously pollinate his most resilient plants with a cotton swab.

His experiments in the greenhouse resulted in the creation of several hybrid plant varieties uniquely adapted to life in the desert. He gave one of the resulting dragon-fruit varieties Alexander’s childhood nickname, Falco.

An aerial photo of the Falkenstein home. David Blakeman/nyt

“When people asked me what my husband did, I would tell them he was a horticulturalist,” Jane Falkenstein said. “I never said that he was an ophthalmologist because he was very dedicated to his garden. It wasn’t his profession, but it was his love.”

In 2008, Falkenstein was diagnosed with cancer and told he had 18 months left. He lived for seven more years. A few days after his death, Alexander took over as caretaker of the garden, giving himself a year to figure out what to do with it.

“I knew that if we didn’t invest some time into maintenance and strategy, the problem was going to grow exponentially,” he said. Working in the garden three days a week, he quickly realised that he knew little about the art and science of rare fruit cultivation. Many plants in the garden required considerable attention. Shade and frequent pruning were a must. Freezing winter nights also presented a substantial challenge.

Alexander Falkenstein turned to the Arizona Rare Fruit Growers, a group of amateur pomologists that his father helped found in 1995. As of January, the group had more than 5,000 fans on Facebook; it regularly hosts events like “Mulberry Taste-Off!” and “What R U Growing, and How To Propagate More!” Many of its senior members have fond memories of Falkenstein’s technical approach to the hobby, and his gifts of fruit and plant cuttings.

Alexander Falkenstein pruning a tree in the backyard garden his father created. photos: David Blakeman/nyt

For many rare fruit enthusiasts in the Phoenix area in the 1980s and ’90s, Falkenstein was the first to demonstrate that it was possible to grow these incredible plants in the desert.

“It was as natural as breathing for him,” said Ruth Ann Showalter, a longtime member of the growers’ organisation. “He was a great teacher, and the group isn’t the same without him.”

In many ways, Alexander Falkenstein picked up where his father left off. He visits rare fruit growers at their homes, and has a rare-fruit garden of his own with mango, banana, loquat, peach and citron trees. He gives away all of the fruit, and shares what he has learned at growers’ meetings.

“The objective is to share all of this knowledge and fruit,” he said. “The strategy is to grow things that I really enjoy so I can keep it all going.” (He recently gave several mangoes to the Phoenix Suns’ executive chef, Brendan Ayers, who used the fruit to make salsa for the team.)

Like many rare-fruit growers in the Salt River Valley, Mr Falkenstein fears that worsening drought conditions will force them to change their approach.

“We try to minimise water loss by ensuring that our soil is healthy,” he said, adding that he has removed plants that require more water, including his father’s banana trees. “We use a lot of mulch and wood chips, which can lead to a 30% to 50% reduction in water needs.”

He tries to be realistic about his gardening — there is only so much he can do to keep the plants alive and to keep the yard manageable for his mother.

In many ways, his efforts are a continuation of his father’s work. “My father had a great reputation that he earned over a lifetime,” he said. “If he were alive today, I think he would be proud of how much his generosity lives on.”

Mangoes in the backyard garden created by Dr Alois Falkenstein. David Blakeman/nyt

Alexander Falkenstein. His father was the ophthalmologist Alois Falkenstein. David Blakeman/nyt

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Copyright: © 2022 by The New York Times